A few weeks ago, I wrote a LinkedIn post about the danger of “false prophets of personal growth.” You know, the ones who promise transformation through a single event, quote, or moment of insight.

The idea that change is event-driven is good marketing, but bad advice. Every evidence-based model of personal change tells us it doesn’t work that way. These “life-changing hooks” have become so pervasive that it’s worth unpacking where they go wrong — and what actually works.

The Allure (and Danger) of “Life-Changing” Hooks

Scroll your feed and you’ll see them everywhere:

“The quote that changed my life.”

“This cured my overthinking.”

“The moment everything shifted.”

They’re effective marketing devices — short, digestible, and emotionally charged. They resonate because they promise what we want to believe about change: that it’s instant, dramatic, and transformative.

But we’re being sold a false picture of how personal growth actually happens.

To be fair, events can spark reflection. A conversation, a loss, or a new challenge can help us see something we hadn’t before. But let’s not confuse insight with change.

The reality — supported by decades of behavioral science — is that meaningful personal growth is iterative. It unfolds in cycles of trying, failing, learning, and re-engaging. Its a process, not an event.

What the Science Says

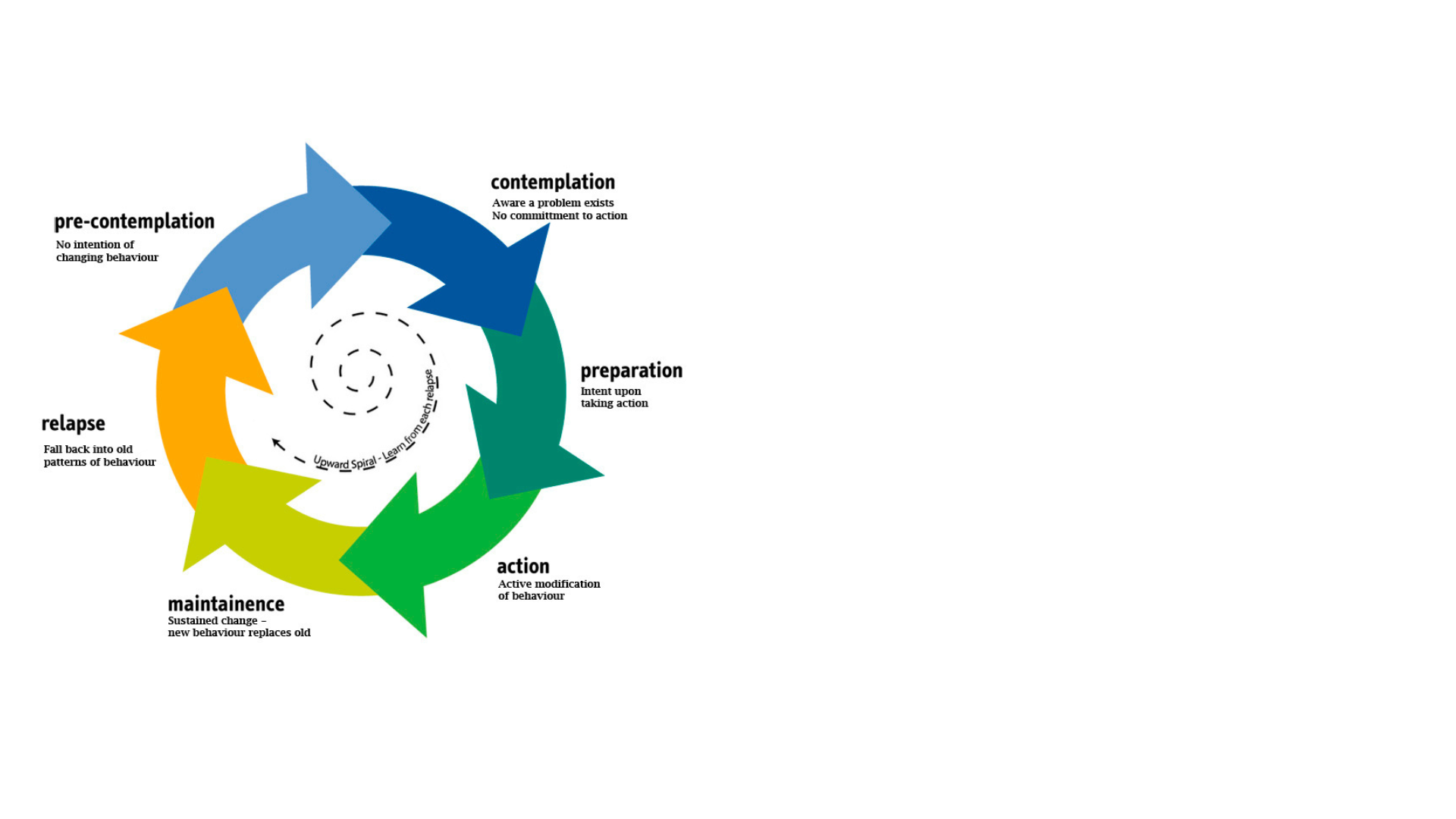

The Transtheoretical Model of Change (TTM) offers one of the most widely studied frameworks for understanding how people actually change. It rejects the notion of change as a single leap, by framing changes as a continuous loop through discrete stages:

-

Precontemplation — not yet considering change

-

Contemplation — starting to recognize the need for change

-

Preparation — planning or experimenting

-

Action — actively engaging in new behavior

-

Maintenance — sustaining the new behavior

And then, often, a return to earlier stages through regression or relapse.

This model applies equally to quitting unwanted behaviors (like smoking) and starting positive ones (like exercise or journaling). Examples include:

-

Falling back into old habits while trying to quit smoking or drinking

-

Missing workouts or breaking diet routines while trying to start healthy habits

-

Stopping creative projects like writing or painting, only to resume later

A Personal Example: Writing a Book (and Relapsing)

A few months ago, I began writing a book — one that explores the science and philosophy of striving: how to pursue ambitious goals wisely, without sacrificing wellbeing, and in a way that aligns with our values and sense of meaning.

The process started strong — early mornings, focused sessions, real progress.

Then, gradually, I stopped. I haven’t returned to it… yet.

I’ve kept writing in other ways (this post is proof), but not on the book itself. Looking back, I think I was daunted by the scope of the project and the long, uncertain path ahead.

The topic came up recently while cooking with a friend, a psychologist and athletic performance coach, who’s in the process of writing a book. I was really curious about her experience of taking on this monumental task, so I asked her about her process, which she told me about. Then I mentioned, “I’m thinking about writing a book.”

She smiled and said, “So, you’re in the contemplation phase.”

I laughed, knowing that “contemplation” was one of the TTM stages, and said, “I think I’m in pre-contemplation.” I went on to describe how I had started and then stopped. We joked about where I was in the stages of change model (which is a really cool and nerdy thing to do). It was a fun and funny conversation, but as I reflected on it later, I realized how helpful it was to frame the start and stop of book writing I had experienced in the context of the TTM.

Rather than failing as a writer, I’d simply looped through a cycle of the stages and regressed to an earlier stage. She was right, I was in contemplation (recognizing the need to change), but only because I had regressed there. Regression wasn’t the end of the story (unless I made it so); regression was part of the process.

The Role of Relapse (or Regression)

Relapse (if you’re trying to stop something) or regression (if you’re trying to start something new) isn’t failure. It’s feedback.

Behavioral science views these setbacks as natural parts of the process of change and as essential providers of feedback. Each setback reveals something valuable:

-

What triggers resistance?

-

Which motivations fade under pressure?

-

What structures or habits are missing to support progress?

How we perceive failure really matters. As Albert Einstein put it,

“Failure is success in progress.”

When we see relapse as defeat, we retreat. When we see it as natural (even expected), we have an opportunity to learn and re-engage.

The only real failure is mistaking relapse for failure itself and failing to restart as a result (if we’re committed to doing the thing).

For me, that means returning to the page not as someone who “failed to write,” but as someone still becoming a writer — and building the routines to support that becoming.

Reframing Your Relationship With Change

The key to personal growth is establishing a healthy relationship with the process of change. It’s not about avoiding setbacks; it’s about making setbacks matter by taking each as a teachable moment.

- Don’t wait for the “aha” moment. Real growth happens in quiet repetition, not cinematic breakthroughs.

- Don’t shame yourself for relapse; expect it. Progress is rarely linear. When you slide backward, treat it as a signal to recalibrate and an opportunity to re-engage.

- Lean into iteration. You don’t need to be perfect; you just need to choose whether you will stay in the process. If necessary, start again, a hundred times if you must.

- Build structure. Small systems and predictable routines make re-engagement easier when motivation wanes.

- Practice self-compassion. Treat setbacks as part of the work, not proof you’re incapable; how you talk to yourself after a regression shapes whether you return.

- Beware of shortcut marketing. The “quote that changed my life” might sell and make you feel good when you read it, but it won’t build a habit.

The truth about the dynamic process of personal growth isn’t convenient; it demands humility, persistence, and self-awareness. When we look for miracles or instant transformations in events, quotes, and anywhere external to us, we yield our agency to the event, when in fact, the power to change resides in us — in our daily choices, our persistence, and our willingness to start again.

Wisdom is in understanding that change is messy, yet striving to grow regardless.